I came to Elsewhere Studios looking for new inspiration. I was born in the swamp, I’ve lived most of my life beside the swamp, and I make artwork about the swamp. This is a subject I am very passionate about, but I really needed a new environment to explore and to influence my artwork. Elsewhere Studios was a perfect place for me to begin new research, because the mountain landscape is so different from the Louisiana landscape. Elsewhere Studios also provided me with solitude and all the time in the world to make artwork. Because I arrived at Elsewhere in May, I got to witness all the flowers blooming, the inviting warm sun and cool nights, bike rides and picking wild asparagus. These humbling experiences were very grounding and sobering. The people of Paonia are just as wonderful and welcoming. All these experiences are fodder for my future artwork. I left a little piece of my heart in Paonia and I took a little piece of Elsewhere back with me to New Orleans.

Emily Cannon

There’s something a bit trite about saying ‘I found myself in Elsewhere Studios’ but it’s definitely something that happened. It starts around two in the morning, after a day of not leaving the apartment because you’re scrapping that one illustration that’s been bothering you all day. Even if the first one looks fine, you know you won't be happy until you try to draw it again. At this time, I think I’m the most ‘myself’ I will ever be, surrounded by cups of ink, water, and coffee, reading a passage over and over again until I can pluck out the dissonant word. There’s such a satisfaction in jumping so completely into your work and being completely submerged without interruption. I don’t think this could have happened if it weren’t at Elsewhere.

Not to say I didn’t leave the apartment. I was extremely fortunate in the company of both fellow residents and staff, who made the bar trips, karaoke nights, and my entire stay all the more memorable. Perhaps it was because of my brief stay, but there’s something wonderfully surreal about Paonia, as if the set from a spaghetti western was yanked into the 21st century. Most everyone seems to know each other’s name, a restaurant festooned in doilies opens at the turn of a dime, a pack of dogs runs rampant through the local bar in the small hours of the morning. At the heart of this is the residency itself, which looks like an enchanted patchwork house formed from driftwood, doors, and ceramic tiles.

What luck it is then that I got to see the residency come to bloom. After three years in Los Angeles, I realize what a gift it is to have a backyard and Elsewhere’s is positively thriving. I watched as armies of irises sprouted in front of my door. I discovered a secret patch of rhubarb in the backyard, the leaves big green platters hiding brilliant stalks. Before this, I had only seen poppies from a distance flecking fields with spots of crimson. Here, they bloomed outside my window. Their blooms so vivid they looked straight out of Oz, their size as big as kittens.

Speaking of kittens, I can’t forget to mention Tomatoes, the ambassador to all the studios. Regularly he invited himself into my workspace and circled my chair like a shark until I let him sit on my lap. He had little respect for my work, which is humbling in a way, especially when I find a little paw print square in the middle of a drawing I had just finished the day before. The morning I left, rising at a time some would call unholy, he was there to walk us to the car.

My time at Elsewhere peeled back the skin I had grown over the bones of who I wanted to be. I found that this month was a much-needed break in my life and possibly the healthiest choice I could make for myself. For a first residency I couldn’t ask for a better experience and can only hope it won’t be the last time I visit.

Thank you so very much!

Wyoming by Chelsey Becker

In the photograph, a newly green vista rose to meet asundering hills that melded into hazy mountain peaks disappearing into a vast firmament dusty with clouds. Below, yellow green grass twisted in the plains, idly stroking the breeze like fingers upon a face. Browned and sun-golden buffalo held still in the field for a short time with their massive, bovine heads lowered to the young sprouted stalks. After a time, I imagine that the creatures trekked through the plain, basking in the spring sun and flicking their tails at buzzing insects as they went, moving on at the urging of their wild instincts.

Desolate. That’s what my mom said when I declared my intention of driving to Wyoming, a desolate place. But it was the state that she had lived in for two years, the state she had left Arkansas for. Come to Wyoming! Her older sister who already lived there had said. There’s lots of men! It was the state she had met my dad in shortly after she moved, the least populated one in the United States. It should have meant something to her at some point. She hadn’t really gone to look for a man, but she found one anyway. I wasn’t going to look for one either, but I was going to look for something just like she had.

She had gone during the big moves of the early 1980s, seeking freedom and a new beginning. What was I looking for there? I knew she wanted to ask, dare me to say it to her, but she was too scared I would actually tell her. An apparition, spirit, memory, or something along those lines. That’s what I wanted, and she knew that without me saying. But I told her I just wanted to take some pictures for my paintings. I could diddle some landscapes from them in oil paint or something. Place pictures of them from then on top of the land and tell a piece story from their time there. And that’s true, but not the whole truth. I want to stand in a spot that he stood in. I want to see if the trailers they stayed in were still there. I want to see the places along the roadside they stopped to take pictures at. Above all, I want to see if he is there in one form or another.

Odd though it may be, I wouldn’t actually mind seeing his ghost. My aunt, his older sister, took his aging yellow Labrador retriever, Maggie, home with her to Minnesota after the funeral. Maggie is old and fat, very fat. Though not as fat as she was a few years ago when I used to call her Sausage due to the roundness of her girth and roll of fat over her tailbone. Dad, used to his former dog that had to be part Malamute, fed her a lot of food. When his sister Sheri found out, she made him stop and take her outside more. Maggie is, miraculously, still alive but with a lamed jut of a walk as she now helplessly follows after Sheri with my dad gone. Anyway, Sheri claims that Maggie has gotten up multiple times in the middle of the night to follow his invisible spirit into the room he slept in when he came to visit then lays down on the floor next to the bed, just like she used to. While I was happy that Sheri told me that, I find it hard to believe that he would pay his dog a visit and not me, his only child, his only daughter. I was the one that made him get that dog in the first place when I was twelve-years-old.

I am not the praying type, and I am not very religious, inadvertently just like my dad and unlike my semi-Baptist mom, but I prayed for a very specific request the very night he died and haven’t stopped since. Weeks went by then months, now getting close to a year, and every night I prayed for a sign, any sign. Also, I am pretty oblivious, so I asked that the sign be blatant. I don’t disbelieve in ghosts and have often found the possibility of them exciting, having watched ghost television shows since I was a child. My boyfriend and I have even toured haunted locations in towns that we visit, Eureka Springs, New Orleans, Little Rock. Jared has felt chills and presences from something supernatural, but I never have. If there was a ghost about, it would have to knock me upside my head to notice it, and I told God or whoever as much in my prayers. However, I may have just received a sign, and it, coincidentally, came in the form of yellow lab, though not Maggie.

I find that dogs often mark important moments in a person’s life. For example, not long after my mom met my dad in Wyoming, she got her first dog that was all her own. It wasn’t a childhood pet or a family dog, it was hers, a fluffy black puppy that she named Bear. Later, when my parents moved to Phoenix, Arizona, they got another dog, a large black and tan dog they named BJ. For me, my first all-my-own dog came when I was in my last semester of college, working around the clock, locked in my room, and lonely, unsure of how life would be after graduation. While on a visit to my mom’s home in Oklahoma, I saw an ad for a fluffy, honey-brown puppy. I also named this dog Bear, and it couldn’t be avoided. I had liked the name Maple, but Jared said it was too girly. Now this puppy, being an Australian Shepherd, didn’t have a tail. Also, she was born on a backwoods farm during the Oklahoma summer and kept outside because she was supposed to be a cattle herding dog, so she had learned to lay flat on her belly in the dirt to keep cool, looking just like a bear skin rug. This made her Bear Becker III, because BJ stood for Bear Junior. And after my dad died, I got another puppy, marking another sadness in me. However, we did not name the puppy BJ, we named her Copper.

Maggie, on the other hand, was a pushed blessing I put on my Dad. After my parents divorced, my dad took BJ since my mom got me. Bear the First had died before I was born from poison in our neighbor’s garage in Phoenix. When I was about twelve, BJ died of old age and I quickly recognized the hole in my dad’s life with BJ gone. At the time, I didn’t realize that BJ was the last link he still had to my mom and the life he had before that was happier. He had never remarried, and if he dated it was never serious enough for him to tell me about it. He had followed us to Arkansas from Arizona but had decided Arkansas was close enough when we moved to Oklahoma. Or maybe he was told to stay put. At the time, when BJ died, I just thought my dad needed a dog.

Shortly after BJ died, he came to see me. As was our routine for years, up until the day he died, we planned to see a movie. We both had a passion for movies, and we were both really good at guessing the plots, whispering to each other what we thought was going to happen next. When I was younger, I would sit on his lap during the movie, leaning against his chest. I still remember clearly the visit when I slipped off his lap and into my seat, deciding for myself that I was too old when I noticed no other child was doing that. Now, I think about how that must have stung him. On the way to the newly built theater in town, I saw a sign for yellow lab puppies for sale. We had time before the movie, so I told him to pull over because I wanted to see the puppies, a plan already forming in my young mind. We pulled into a semi-dilapidated house with a rusted, chain-link fence in the back where we could hear the dogs yapping. I picked up a puppy, petted it, and told him he needed it. Still fairly young, I had no qualms pointing his loneliness out to him. He smiled slightly, almost shyly, then came back and got her after we saw the movie. Later, he named her Maggie for the Rod Stewart song. Fourteen years later, she outlives him.

I have been in Paonia, Colorado, for nearly two weeks when I discovered that Lyman, Wyoming, wasn’t terribly far away. It was only six hours away, which was nothing compared to the fifteen hours it had taken me to drive to Paonia from Oklahoma. I had to go, needed it, needed it badly. The instinct to travel there was deep and almost violent. After months of wanting to feel just an inch closer to him, I was closer to Wyoming than I had ever been, and it’s essentially where I began. I called my mom after the revelation, unable to get ahold of Jared who had been my first choice to tell, only for her to pour doubt onto me and smolder my enthusiasm. I knew that she would do that, but I had called her anyway. She was currently on vacation with my stepfather in coastal Alabama, sitting on a beach, and celebrating twenty years of marriage. The first thing she said was desolate. It’s desolate there, Chelsey. I don’t know.

I didn’t call for permission. I called because my excitement burned, and I needed to share it. I should have known she wouldn’t have caught it. She dropped it like a hot potato. Anything relating to my dad, she shriveled away. On the other end of the phone, I could picture her wide, almost debatable eyes and crinkled forehead. She pretended her first marriage was a quick affair that resulted in me then dissolved just as quickly. As a child, I swallowed that lie like brownie batter. However, after putting a timeline together through clues I gathered over the years, I know that’s not the case. They were together for about thirteen years before they divorced. I was around four-years-old. They hadn’t been married for thirteen years, but they had together since 1981. And from the hundreds of photos I’ve sequestered and studied thoroughly, they had been in love. And I know my dad never stopped loving her. My grandma, Mary Lou, his mom, told her so at his funeral without any malice. She just said it like the fact that it was.

Mom didn’t say I couldn’t go, because she knew that she couldn’t. But she also knew that she didn’t have to say I couldn’t go. She could bend me to her will most times with just the tone of her implication. I don’t believe she was actually worried that it was unsafe for me to drive there alone, she was uneasy of me showing interest in my dad when she refused to long ago. I wish Jared would have answered when I called him first.

As my resolve started to soften like sodden wood, still strong but spongey on the edges, I looked out of my rented cottage to see the foot of a dog disappearing up the stone steps. I was in the mostly enclosed, overgrown backyard behind the main house. Transfixed, I opened the door. A blonde tail whipped around the wall surrounding the artist residency. The dog was sopping wet and left dark pawprints on the steps. I quickly followed, passing the blossoming irises and poppies in their unkempt beds, and whistled hoarsely through cracked lips. I walked through the mirror mosaic arch in the wall, seeing my wonder reflected back in fragments. Then I saw him fully. He was alone but had a worn, reddish brown collar. He had walked in front of my secluded cottage in an even more secluded town right when I needed him to. He kept walking.

I made a guttural sound that was between a wheezy whistle and indiscernible greeting. The dog turned and looked at me. I stood still. He was taller than Maggie and less fat and at least six years younger. Not a pup, but still a healthy age despite a greying face. He didn’t come towards me. He just looked and dripped water on the gravel. He didn’t bark. He didn’t move, and I didn’t either.

My eyes felt full and heavy all of a sudden. I took a step forward and he blinked one quick blink like he was coming out of a trance, like he had just noticed me. My hands wavered in the air. Unsure if he was a nice dog, I walked back to my cottage.

Emma Balder

Within the first week of being in Paonia, coming in full force, I completed about 15 fiber painting studies, little creatures inspired by the many wonderful, unique beings in this eclectic town. Once I felt like I had a good momentum going, this production slowed to the gentler, peaceful pace of the town. I began focusing intently on my 4-foot large round fiber painting (see photo), a new challenge for me in this detail oriented process.

By the end of week two, I had fiber painted almost to the edge of my round substrate, but still needed to go back in with graphite and acrylic once this part of the process was complete. At this point, I came to the realization that completing this painting in one short month (while normally working much smaller in this material) was a lofty ambition. Upon accepting that this piece would take me at least an additional month, I felt myself succumb to the power of the slow process. In turn, this not only gave me the space to create a deeper relationship with my painting, but to also establish deeper relationships with those around me.

Below is a photo of some small studies, and an in-progress shot of my 4-footer. Additionally, one of my favorites, a photo of Yifan playing around with one of his balancing ceramic pieces. These works balance delicately on rope – I love how this forces the viewer into the fear and fragility that is present in his work.

Erika Lundahl

The Road to Athabasca: Lessons from the Lichen of Jackman Flats Provincial Park

Below is an excerpted draft from the book I'm working on about the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which was my artistic focus at Elsewhere in February 2018. In 2015 I visited one of the 10 provincial parks of British Columbia that has been set to have its borders gerrymandered to accommodate the pipeline as part of the Road to Athabasca pilgrimage. You can follow more of my writings and music at erikalundahl.com or support me on my Patreon at www.patreon.com/erikalundahl

Thank you Elsewhere for helping support my artistic journey! -- Erika

***

Barbara Zimmer is the fairy godmother of Jackman Flatts Provincial Park, one of the ten parks in British Columbia that could have its borders redrawn to accommodate the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion. Trained as a botanist, Barbara and her husband moved to Valemount, British Columbia in 1975. She soon became enamored with the biodiversity of old growth lodge pole pine trees and lichen species in the local wooded area where locals would cross-country ski during the winter. She’s spent over half her life now protecting them.

Forty-years later, and Barbara’s advocacy for the park has helped transform it from a neglected and unused strip of land owned by the Ministry of Forestry (the land was too unstable to be forested), to one of British Columbia’s Class A Provincial Parks.

We meet Barbara at the trailhead of Jackman Flats after a relatively short day of riding from Blueriver to Valemount. This is a “Cinderella Park” she explains—underfunded and little utilized by the public except by the locals. But left alone, she says, is just the way it should be. She gives us the cliff notes on the park’s geologic history in one swift, powerful monologue:

“Go back 11,000 years ago and the place was full with ice, wall-to-wall ice in this whole valley. And if you ever get a chance to look down the valley you can see. It’s that glacial, U-shaped trench, and there was huge glacial movement down the trench. And when all that melted away about 11,000 years ago it left a huge lake down there. And as the lake dried up, the prevailing wind from the southwest here picked up the sediments from the dry lakebed and they blew them. So you had an order of events. The heavy particles dropped down here. The small particles dropped out further North. And you way North, they got clay, real small stuff. We’re in the middle, we sort of have nice soil, its kind of silty. And here they got the sand, and Valemount got the sand."

Over thousands of years, the sand of what is now called Kinbasket Lake deposited into over a hundred dunes throughout the Jackman Flats Provincial Park. Now, the dunes are somewhat stabilized, though still over half of them regularly shift with the wind and weather.

“Any major disturbances such as a pipeline could easily cause the dunes to erode and drift across homes and highways.” That’s what Barbara told the National Energy Board in her expert statement on why the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion should not be built through the middle of this park. The existing Trans Mountain pipeline, which we’d followed along with that day, was just across Highway 5, outside of the boundaries of the park.

***

Barbara is a civil servant to this small patch of wild, someone who has been called to act as protector, historian and translator for the voice of this unique 1130-acre bioregion. She speaks for the park’s interests as a passionate lawyer for her client in court. We follow her through the park single-file, along a winding footpath, through groves of dry but hardy lodge pole pine trees, and a crusty ground littered with small, berry-covered shrubs and yellow flora. They don’t look it, but many of these trees are 250-years old or more, she tells us. “Their growth rings are so tight because they’re growing in such bad conditions.”

Clinging to sand dunes with very few accessible nutrients has made these pines resilient, able to sustain an environment defined by instability and scarcity. When the pine beetle came through, an invasive species to the region that kills lodge pole pines and other trees, Jackman Flats were impacted, but on average, they weathered the invasion much better than other areas of British Columbia.

When a pine tree is under attack by beetles, it releases pitch to try and drown out the beetles. She takes us to one pock-marked pine, with a long stripe of burn running vertically up the trunk, revealing a dark inner core. This tree survived two large forest fires, but lost the fight to the pine beetle, invasive to this region.

Barbara suspects that the age of the trees, and the incredibly slow rate of growth is what has protected them from the beetles invasion that has now passed through southern British Columbia and is spreading north to the Boreal Forest as the temperatures have warmed with climate change. For now, the remaining trees are believed to be relatively safe from the beetles.

“These trees fought hard. They did well.” Barbara tells us proudly.

When the Parks Canada wanted to come log the threes trees felled by the pine beetle invasion, she wrote to them and told them not to.

“I told them you just leave the pine beetle alone. Pine beetles have been with pine trees for hundreds of millions of years. This has all happened before. There’s only one thing different now, and out of balance, and that’s us. We’re the only thing that’s messed up really.”

***

Even though Jackman Flats Provincial Park is only 1130 acres, it’s the only wild left on the Robson valley bottom that’s still in one piece. The rest of it is in private hands, and is mostly developed into farmland. It’s just not enough space, she says. There used to be Nightjar birds here, but Barbara hasn’t seen them in a long time. Still, there are over 200 species have been counted to date by herself, other volunteers, and outside experts that travel to see the unique ecosystem held within the park.

“Even though this is a tiny little park, it’s all that’s left ecologically intact for all the things that need to live here.”

Lower in the park, the ground is covered with Kinnikinnick or Pudding Berry. A red berry with a mealy texture favored by grouse and bears, its name is taken from the native word for “smoking mixture,” which it is often used for.

On another pine tree, Barbara gently fingers wispy threads of grey and green old man’s beard and horse hair lichen to show us an organism that is both plant and animal: Lichen. This is the marriage of fungi and algae, she tells us. To teach us how that works, she grabs a hold of my arm, playfully.

“Okay. You be the algae.” she says to me with a sly smile. “You’re green and you have chlorophyll and you can make food.” She points to herself. “I’ll be the fungus. Hi.”

“Umm, hi.” I don’t know what else to say, but I like this game already.

“Okay, Now I punch right through your shirt. Not under your skin though, I don’t want to hurt you.” She mimes punching into the side of my shirt gently. “Okay, make food.” She orders, urgently. “Food, food. Make it.” I start miming mixing some sort of food in a bowl.

“Good. You’re photosynthesizing, you’re making sugars. And I take 40% of them. I just take them and I use them and I grow. Keep working. Making the food.” Now she softens, and puts her arm around me. “So, I sort of surround you.” If you cut lichen under a microscope, you can see the little green algae cells, she tells us. “The fungus has them all lined up like little rows of cabbages, right up near the tops so they can get the sun.”

Botanists used to call this collaboration “mutualism.”

“Now we call it controlled parasitism.” She tells me. “Because if I take too much from you, what’s going to happen?”

“I’ll wither away?”

“Exactly right.”

***

When we reach a high point on one of the dunes and the path widens. It really is just sand beneath our feet. Here, the trees thin. The ground looks crusted and dry, but with muted pastel colors winking out from the sand.

“Is that Cryptogamic soil?” Derek asks, excited.

“Exactly right.” Barbara leans down, pointing. “Cryptogamic means hidden life.”

Down on my hands and knees, I can see more clearly. Embedded in the rolling sand, crystalline structures of muted greens, blacks and grays, reds and purples coat the ground, like a homemade knit cap made of the thinnest knitting needles in the world. Here mosses, fungi and algae overlap, connect together, creating a co-dependent network of life. The grey patches, she tells us, are a lichen unfound in anywhere else in British Columbia.

In 1995, “Coral Lichen” was discovered in Jackman Flats Provincial Park. Stereocaulon condensatum—the grey patches of lichen Barbara showed us—were discovered by Trevor Goward [E1] on the tops of one of the smaller dunes. Curator of lichens at the University of British Columbia, he has since made many other species discovery in the parks and said of the area:

“With forty years of lichen study behind me, I can say without fear of contradiction that Jackman Flats is one of the top ten lichen hot spots in British Columbia. The lichen flora there is a regional and indeed a provincial treasure that truly deserves the protection it has received under B.C. Parks.”

Some of the lichen here take a hundred years to grow one inch. You can’t mitigate this. If you come through here with a pipeline, it’s gone.

“This dune community is not found anywhere else. Period.”

The language used to describe the characteristics of cryptogamic soil is surprisingly intimate and humane. Any particular collection of plant and animal life that make up Cryptogamic soil is called a “community,” due to the interconnected support network of different, co-dependent organisms that rely on each other for survival. These communities of interdependence have figured it out: When life gets hard, get organized.

Scientist Robin Wall Kimmer speaks passionately about lichen’s ability to collaborate in her book, Braiding Sweetgrass: “Balanced reciprocity has enabled them to flourish under the most stressful of conditions. Their success is measured not in consumption and growth, but by graceful longevity and simplicity, by persistence while the world changed around them. It is changing now.” On these dunes, the particular make up of lichen and algae is found nowhere else.

Right now cryptogamic soil is growing slow and quiet across the West and the Southwest of the United States, as well as the plain states of Canada: Southern Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona all host this hidden life.

Derived from the Greek, "Cryptogamae" (kyyptos meaning “hidden” and gameein meaning “to marry.” Hidden marriage.

More exactly, it means “hidden reproduction,” because unlike other plants that replicate themselves through dispersing seeds, these communities send out spores to expand their reach. They are many and one.

The New York Botanical Garden defines controlled parasitism as a relationship in which “the organisms in association are in equilibrium and there appear to be no or minimal damage or disruption to the host organism.”

That’s how fungi and algae behave when they make lichen, conspirators of parasitism that serve to sustain both plants. And they’ve been doing it for 400 million years. The lichen as an organism is also parasitic towards other plants, animals and trees; sustaining on the bark of the pine.

Barbara shows us a pine tree with more than a dozen different-colored lichen species on the bark, all within just a few inches of one another, and shakes her head.

“We’re the ones that haven’t been here very long. We’re the parasites that haven’t learned yet that we’re taking too much from our host and we’re in trouble because of it. But we haven’t been here long enough. 2 million years is not very long in the scale of things, and we haven’t been here as a species for more than 200,000 years. We’re so new. We’re the new kids on the block and we haven’t learned yet. Parasites eventually learn not to take too much. Because if they do, they kill the host."

Alma Shoaf

Nestled in the North Fork Valley, to the west of the draped wound of the Rocky Mountains, is the town of Paonia. It is well over a mile in elevation, has a population under 2,000, and it is surrounded, cut and besieged by railroads, fruit orchards, coal mines and cattle farms. While it’s possible that the botanist Terence McKenna may have opened a vortex (of what kind, no one seems aware) in the basement of what once was the General Electric building, now the home of Elsewhere Studios, it is certain that mountain lions, bears and coyotes do walk the mesas in watchful hunt… although, to a visitor like myself, they are very nearly as invisible as McKenna’s alleged vortex.

I had never visited Colorado, although as a huge fan in college of the “Denver Music Scene”, I had a great want to. Those seem now like childish fantasies filled with Stetsons, whiskey swigging, and crooning to Jay Munly’s off-beat banjo thrashing. In contrast, my one-month residency in Paonia was very real, and perhaps one of the most sobering and grounding experiences of my increasingly adult life. I found the kind of solitude that a recluse like myself only dreams of, and was able to weave connections with a thread that I believe will continue to send vibrations in every direction for a long time to come.

Arriving for my residency took a tad bit of effort, as I hate flying and knew that I would miss my cat terribly (and my partner, too). It took me a good bit of the first week to quell my anxiety and wiggle into my space, ripping the first few pencil lines out of myself like a baby tooth dangling on its last thread of flesh. But, of course, it got easier. And easier. Until I found myself trapped in the studio past midnight by my own newly-industrious hand (I am not normally a night worker). By the end I had created one of my favorite drawings I’ve ever made, I think. It will, no doubt, become one of those incongruencies in which my assertion of its quality will be met with a resounding breath of indifference at best, perhaps a universal “meh”, but so it usually goes.

Since returning home, I find I am still staring down the lengths of ditches and creeks, noticing rocks and the odd plastic bag skipping with a sense of dubious freedom down the road. All the quiet, unnoticed things that I collected in my camera, sketchbook and mind in Paonia are also here, and are everywhere. The human beings that walked these same valleys long before this country was and – despite the past’s undeniable maliciousness – still do; coal miners and their memory carried into the future by their children; bones, trash, breath, metal, the most fragile, sleeping flowers – they make up the great, strange composite of America, of its history and tragedies and of the odd success along the way. It can make me sad, as my walks along the train tracks sometimes did, but in a strangely pleasant and hopeful way. It can be recorded; it can be deconstructed, reconstructed, constructive. If an artist residency is meant to give space for creation, Elsewhere gave me that in both an external and internal landscape that I hadn’t seen yet.

And I really, really, really miss Tomatoes.

Ellie Schmidt

Paonia's Potluck Season

When I first arrived to Paonia in the dark I was greeted by the holiday lights and nativity scene at the top of the hill. The town seemed sleepy but alive, the Hightower Cafe lit up from inside, people puttering around in cars and on foot. However several people during my first few days here called Paonia a "ghost town" in the winter, making me imagine summer days filled with tan people on bikes, drinking fresh juices, farm workers and migrant artists mingling alike.

Every day during my residency I tried to escape the cozy 20 ft radius that I otherwise lived in-- I would put on my boots and wander around town, or to the river park where I would look for interesting rocks and admire all the dry and dead winter foliage. My inner self seemed to take on the spirit of my surroundings; I felt very quiet, observational without judging. In a way I felt invisible, because my stay here was so brief, but I also made it a point to say hello to everyone I passed on the sidewalk. I felt deeply free and happy, but still on the surface, maybe like a stream below a frozen crust.

"Ghost town" as it felt during the day, Paonia came alive for us at night. I went to several potluck-style events during my month here, and people cook as if competing for an amazing prize. The food seems to be totally organic, local (if not from people's own gardens), cooked with a huge variety of creative flavors, and in stunningly copious amounts. I could almost feel the robust food heal all deficiencies from my body instantly.

And beyond the piles of world-class food, the potlucks of Paonia introduced me to the equally high caliber and colorful humans of the area as well. I loved to see both very old people and very young people attend en masse all the potluck events-- I've never experienced this trend in a community, but how wonderful! There was sometimes dancing, sometimes games, but always meaningful conversation and a willingness to ask a stranger about her life and brief stay in Paonia.

At the end of the potluck events in Paonia that I attended, I returned to my bunk feeling full in every sense of the word. Although I would love to experience the bustle of Paonia in the high summer, I wouldn't have traded potluck season here for anything.

Winter Ross

Like some residents, I came to Elsewhere during a transition in my personal life. (Break up with

your partner and become homeless in the process – you know the drill!) I am grateful that Elsewhere was able to accommodate me and even graciously extend my residency at short notice. I appreciated the staff's flexibility and support. Having a home base gave me the time to plan the months ahead. This is not to say I didn't also do creative work: I'm learning to paint again after a long career as a graphic designer and fiber artist; I wrote a new piece and organized a short story collection, just as I'd proposed. I made a point of networking with other artists in Paonia and Hotchkiss. I loved the Meet and Greets to “show off”, get feedback and just plain party, which relieved the isolation one needs for studio work. I read good books, took river walks and had fun going to every cafe and creative function I could afford. And of course, I fell in love with Paonia. I also saw, up close, the challenges of funding and running a residency and despite that, I'm determined to try it myself back where I came from.

Thank you, Elsewhere, for the “home” and the inspiration.

Donna Cooper Hurt

After Being at Elsewhere Studios for a week I was tipped off by a local about the aspen trees on Kebler Pass located on the way to Crested Butte. My drive took me on a climb to over 10,000 feet. There were many places to pull off the road and take photos over the pass. When I saw the white bark of the trees and the blazing yellows of the foliage I knew I had found an area to sink into and work. Here are a few images from my trip that day.

I was lucky to have been at Elsewhere in the month of October and experience a mild Fall with temperatures in the 60's during the day. Paonia, and the areas around did not disappoint. The landscape in this part of CO is beautiful and gave me many places to work and focus on my performative photo series, "Communions."

Thank you Elsewhere!

Aaron Morgan Brown

One day in early September 2017, I impulsively searched for audio clips of Terence McKenna on YouTube. I was vaguely familiar with his philosophical explorations and legacy (being interested in altered states myself), and I wished to deepen my understanding of what he was about. One of the first clips I listened to, a segment taken from one of his lectures, was titled “Nature Loves Courage.”

A couple of days later, I went searching for a short term artist residency. I had a block of time to fill, and on such short notice, I didn’t expect to find anything. On the first page of my Google search, I found an unexpected opening for October at Elsewhere Studios. I applied immediately, and was accepted. By the end of the month, I was on my way to Paonia.

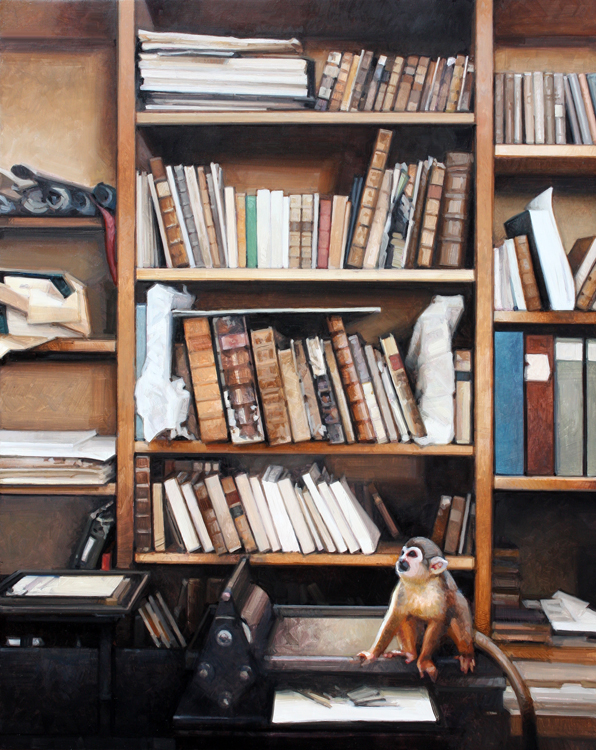

Shortly thereafter, I learned that Terrence McKenna was born in Paonia. I also learned that he had been involved with Elsewhere, and had actually spent time at the house. On the day of our orientation tour, Daniel took us to the community garden, and on the side of an adjacent building was a painted quote, in red letters: Nature Loves Courage. One of the ideas I had brought with me seemed to fit the moment seamlessly, so when I finished the painting (more or less), I titled it thus.

Meant to be? Call it sychronicity, call it a coincidence — I call it a nice affirmation. Elsewhere is like that. :)